“Waves keep coming, that’s the one thing you can count on in life” — Gerry Lopez

Following the easing of the lockdown restrictions, it is clear that the COVID-19 pandemic has created the perfect storm that runs the risk of worsening many of the already poor health indicators in Nigeria. From transport restrictions, to anxiety among health care workers, from stigmatisation to fear, fewer Nigerians are accessing the health services they need — and all this data can be found publicly on the website of the Federal Ministry of Health.

Just like a wave, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has swept across the world at an unprecedented pace. The reported transmission of the disease started in Wuhan, China in December 2019, from a small cluster of cases to over 10 million cases globally and counting. In a world interconnected by easy global travel, the disease quickly spread from Asia to Europe and North America, and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organisation (WHO) on March 11, 2020. The pandemic has been slow to spread on the African continent and there have been many theories suggested for the delayed arrival of the virus on the continent, however it was never a matter of “if”, but “when”. The first confirmed case of COVID-19 on the African continent was reported in Egypt, on February 14, 2020.

The start of the virus in Nigeria

Nigeria reported its first confirmed case of COVID-19 on February 27, 2020, an Italian man who had arrived in the country two days earlier. Subsequent sporadic cases were reported in Nigeria and other African countries, showing that the COVID-19 wave had reached the African continent, with the imported cases coming mostly from international travellers coming from the USA and Europe. Preparations that were being made had to be ramped up. It was felt that the later arrival of the virus should have bought most African countries time to make the necessary preparations in strengthening their health systems. However, in many African countries, including Nigeria, preparations had to be made on the back of an extremely weak health care infrastructure. The Secretary to the Government of the Federation (SGF) and Chair of the Presidential Task Force is quoted to have told the National Assembly that: “I never knew Nigeria’s healthcare infrastructure was in such bad state”

The COVID-19 outbreak has brought in some much-needed emergency funding and other resources into the health sector. These funds, have come the Federal Government, the United Nations, private sector groups, and others. However, most of the funds have been earmarked specifically for the COVID-19 response.

The struggle of Nigeria’s health systems

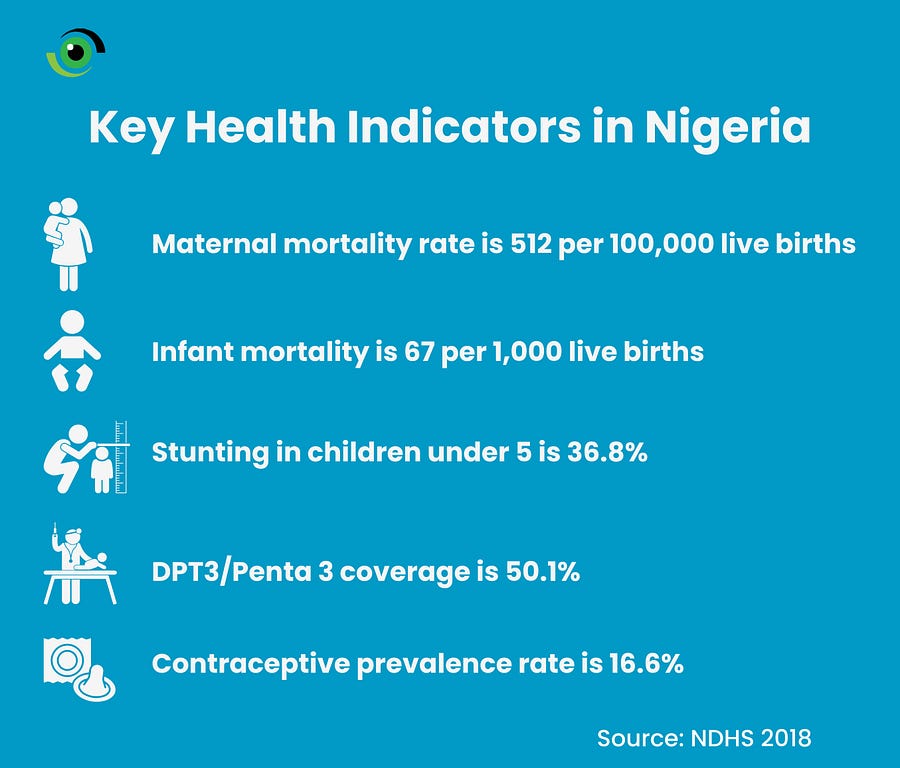

Nigeria has been struggling with some of the worst health indices in countries at similar stages of development. The maternal mortality rate (MMR) is 512 per 100,000 live births, infant mortality is at 67 per 1,000 live births of children 1 years of age, the prevalence of stunting in children under 5 is 36.8% nationwide, the contraceptive prevalence rate is 16.6% and DPT3/Penta 3 vaccine coverage is 50.1% nationwide, although there are regional variations in vaccine coverage. Progress has been made in improving health some of these indices, however this gloomy snapshot of health indicators shows the scale of the health challenges the country is already facing. When the COVID-19 outbreak started in Nigeria, many of the existing health issues took a temporary back seat as the country grappled with the COVID-19 response. These issues may have been put to one side, but they have not gone away.

With rising cases of COVID-19 in Nigeria, the government put in place an initial lockdown in Lagos, Federal Capital Territory and Osun State at the end of March 2020. As a public health response, the lockdown was meant to slow down the spread of the virus, to buy more time to strengthen the health sector’s response. The lockdown initially enabled the Federal and State Government agencies to take early action and implement comprehensive public health measures — such as case identification, testing and isolation, contact tracing and isolation of contacts, as well as continuing the rollout of the laboratory infrastructure across the country.

Patients face challenges accessing healthcare during the lockdown

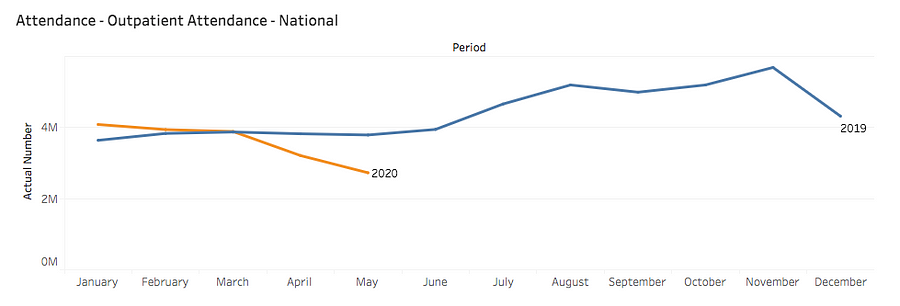

During the lockdown, transport restrictions made it harder for people to access healthcare if they needed it. Looking at the uptake of health services since the start of 2020, there has been a steady decline in outpatient visits at health facilities across the country since March 2020, at the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak, compared with the same period in 2019. People were fearful of visiting health facilities, as they wanted to reduce their risk of catching COVID-19, many delayed seeking care instead choosing to visit local patent and proprietary medicine vendors (PPMVs) and hospitals cancelled elective surgeries and non-emergency procedures.

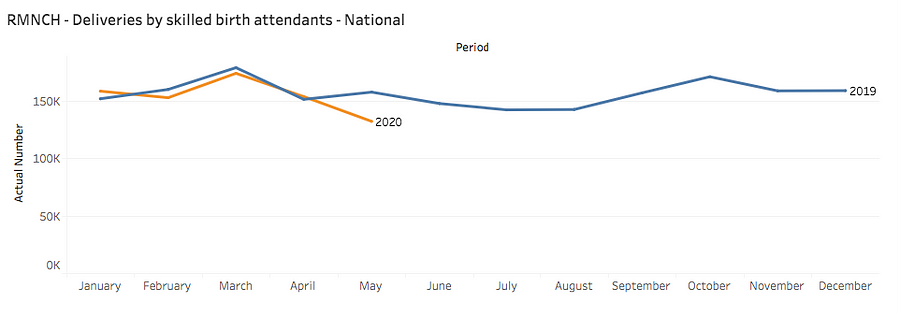

There were reports of health facilities turning patients away for fear that they may have COVID-19, and in the process there were some tragic avoidable fatalities. Some other facilities insisted that patients had to a take a COVID-19 test before they receive treatment. This concern was echoed by the Honourable Minister of Heath during a Presidential Taskforce press briefing in May, when he confirmed that “Latest statistics from the National Health Management Information Systems indicates that outpatient visits has dropped from 4 million to 2 million, antenatal visits from 1.3 million to 655,000, skilled birth attendants from 158,000 to less than 99,000, while immunization has dropped to about half”. He went on to state that “All these have as yet undetermined consequences which the easing of the lockdown should hopefully address”.

How unique is Nigeria in its experience with decreasing outpatient visits to hospitals? Can we say the repercussions of the disruptions in health services may be more severe given our low starting point? The COVID-19 pandemic has thrown the spotlight on the deficits in the Nigerian health sector, as greater pressure has been put on existing facilities, especially at the primary health care level. Many health facilities are plagued with poor infrastructure, and inadequate number health workers and medical equipment.

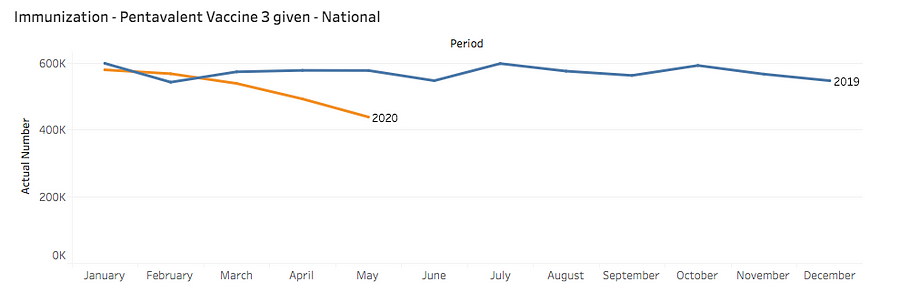

A drop in routine immunisation rates

The drop in immunisation levels is particularly concerning because this could be more disruptive than the pandemic itself in the long term, if children under the age of five die from vaccine preventable diseases. In an interview during the recently concluded 2020 World Immunisation week, Dr Faisal Shuaib, Executive Director of the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) mentioned that “because people were concerned that they many come in contact with COVID-19 cases and because of difficulty with getting transportation during the period of the lockdown, a lot of parents did not avail themselves of the opportunity to vaccinate their kids so there was a lull in the number of parents taking their kids for these services”.

As a result, public service announcements and community engagement were intensified, engaging traditional leaders to encourage parents to continue taking their children for their routine immunisation. The benefits of routine immunisation outweigh the risk of possible infection when taking children to receive their immunisation, if all other protective measures are adhered to. Otherwise, the price we may pay could be a resurgence in vaccine preventable diseases like yellow fever, measles and meningitis and this is a scenario we really want to avoid.

Holding on to the gains made in the malaria fight

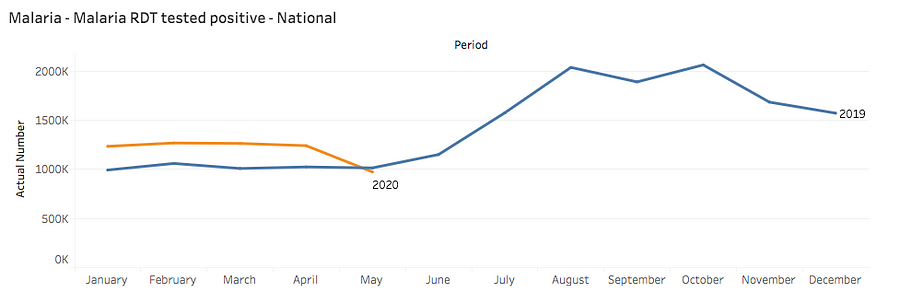

Sub-Sahara Africa accounts for about 93% of global malaria cases, with Nigeria accounting for about 25% of the total worldwide cases. More cases of malaria are reported in Nigeria than any other country in the world. The COVID-19 pandemic risks complicating the fight against malaria. The challenge of people confusing malaria and COVID-19 symptoms was outlined in a Twitter thread by Dr. Adebola Olayinka, National Lassa Fever Research Coordinator at the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC). People are advised to get a COVID-19 test and not to rule out COVID-19 when they have malaria symptoms and a loss in taste or smell. To further tackle the compounding of these two diseases, several strategies have been adopted such as risk communication messaging which has tried to tackle the mis-diagnosis of malaria and COVID-19 by distinguishing the symptoms between the two diseases, as well as integrated messaging led by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Society for Family Health (SFH).

The gains made in the fight against malaria have been enabled by the distribution of long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLIN) into high burden communities that are endemic for malaria. However, the disruption in distribution of the LLINs due to the COVID-19 pandemic, especially during the lockdown could result in more deaths from malaria as patients faced challenges accessing rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and treatment in health facilities.

Health facilities limit services for pregnant women

The drop in births with the assistance of a skilled birth attendant is a real concern. Nigeria already accounts for 20% of global maternal deaths, and the COVID-19 pandemic risks worsening the outcomes of pregnant women. While there is no evidence that pregnant women are at an increased risk of being affected by COVID-19, the decline in antenatal visits, as reported by the Honourable Minister of Health, also paints a dire picture as it was reported that some medical facilities halted outpatient services due to the pandemic. Some private health facilities offered their patients continued care via telemedicine, however these were in the minority.

Pregnant women have continued to face many challenges when presenting at a health facility to give birth or access routine care. There have been reports that in some public health facilities, pregnant women are being charged for the personal protective equipment (PPE) that was to be used when they give birth. In others, health facilities refused to accept new patients that were not registered at the health facilities prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Some required pregnant women to take a COVID-19 test before they were provided with healthcare. All these factors put increased financial pressure on women and this contributed to the decrease in facility births.

What now for the Nigerian health sector?

The COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented and has caused economic, human and social upheaval globally. However, a lot has been said about the opportunity this now presents for Nigeria to really focus on investing and strengthening the health sector. This will require an all-of-society approach involving the government and private sector. The chronic underinvestment in the health sector is being exposed. Less than 5% of Nigeria’s 2020 total budget has been allocated to healthcare, continuing the unfulfilled commitment agreed in 2001 by Heads of State of African countries to commit at least 15% of their annual budget to healthcare.

Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, it is evident that increased funding is required in the health sector and the umbrella of health insurance needs to be opened up to more citizens. Improvements in healthcare delivery would require addressing the issue of access to healthcare, quality of care and financial support for low income families. The co-founder of Access Bank, Aigboje Aig-Imoukhuede in collaboration with the Private Health Health Alliance of Nigeria (PSHAN) has committed to contribute to improvements in the Nigerian health sector. Plans have been unveiled to rebuild one primary health centre in every Local Government Area (LGA) in Nigeria. This is a critical intervention at this time, because primary health care is the foundation of all healthcare delivery and where most people’s basic health care needs should be met. With reported community transmission of COVID-19 at present, it is evident that the community health workers will be the foot soldiers in the fight to contain the current pandemic.

Innovative solutions would need to be found to increase uptake of routine health services. To ensure that people feel comfortable visiting health facilities and parents feel comfortable bringing their children for routine immunization, health facilities would need to ensure that they put in place public health measures like enforcing the wearing of face masks, ensuring handwashing facilities are available and ensuring enough physical distance between visitors. In Kano State, Nuhu Bammali Maternity Hospital, a primary health care centre has used Volunteer Community Mobilisers (VCM) to drive immunisation uptake as they had recorded a decrease in mothers bringing their children for immunization and pregnant women coming for antenatal visits.

Many have asked why there is so much focus on COVID-19, even though annually more people are dying from NCDs, malaria, maternal and infant mortality to name a few. The shutdown of global economies and the race to find a vaccine is a clear indication of the current state of affairs. A concerted effort now needs to be made to rebuild the Nigerian health sector; this opportunity must not be missed.